By Liz Colmant Estes, M.Div. 2017

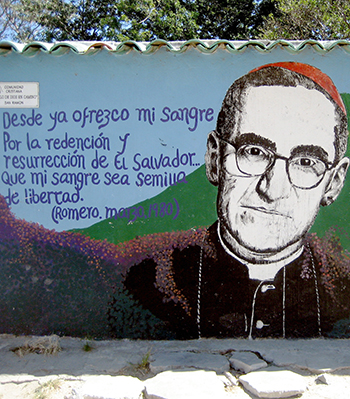

Oscar Romero did not want to die. He was terrified of bullets and bombs and spent his last nights sleeping in an altar chamber in a hospital chapel, praying for safety. Romero didn’t seek martyrdom. As a shepherd, however, he felt obliged to give his life for all Salvadorans, even those who might kill him. “If I am killed,” he told a Guatemalan reporter who asked about death threats Romero received a few weeks before his murder, “I shall arise in the Salvadoran people.” If God accepted the sacrifice of his life, he said, “Let my blood be a seed of freedom and the sign that hope will soon be reality.” Then, on the Sunday before the was murdered, while delivering a sermon on national radio, Romero beseeched his government’s soldiers:

“Brothers, you are part of our people. You kill your own campesino brothers and sisters… No soldier is obliged to obey an order against the law of God. No one has to fulfill an immoral law…I beg you, I beseech you, I order you in the name of God: Stop the repression!”

This January, as El Salvador commemorated the 25th anniversary of its savage civil war, I traveled there with five seminarians and two alums—our instructor Dr. Whit Hutchison and T.A. Timothy Wotring—for Union’s bi-annual, January-term class, “The Liberative Spirituality of Archbishop Romero.” At a hospital for people with long-term illness, we entered the humble, cinder-block home of the archbishop who was fatally shot in 1980 while he said Mass. We toured shrines to other martyrs, including the colleagues of the liberation theologian Jon Sobrino: six Jesuit priests and two women murdered at the University of Central America (UCA) by the military in 1989. We found remembrances, in both places, of Father Rutilio Grande, whose murder in 1977 converted Romero from a supporter of his country’s right-wing government into a shepherd for his people.

Those are the deaths of the famous few, yet Jon Sobrino calls them, “the secondary saints of the kingdom.” By January 16, 1992, guerrilla forces and military leaders finally signed peace accords but 75,000 people had already died—most of them campesinos, poor farmers. When we visited liberation-theology-inspired communities, we were amazed to hear leaders fertilizing their restoration efforts on the holy ground of memoria historica: the historical memory of ungodly mass tragedy. Children sang songs comparing the lives of Monsenor Romero and Jesus of Nazareth—Jesus was a martyr for his people, like Oscar! Salvadorans plastered their church walls with brilliant murals of devastation. Names, photos, and tombs of local war martyrs graced sanctuaries. Church aisles featured Stations of the Cross that mapped scenes from a community’s story of persecution and restoration against the backdrop of Christ’s passion and resurrection. Among the local heroes, ubiquitous images of Archbishop Romero and church martyrs sanctified personal losses, making them holy.

Memoria historica, however, is about life, not death. This became crystal clear to us in the mountain province of Chalatenengo, just east of Honduras, when our van pulled into a resettled village in Arcatao. A handful of small women in white aprons waited for us on the steps of their community church. Along with our backpacks, we each grabbed a six-gallon water jug—more than enough for the long weekend. Across the street loomed an immense pile of corn cobs. Tiny children, two or three years old, and craggy old men rubbed the husks with the back of their wrists, popping kernels that would be ground into flour. Older children and teenagers helped carry our baggage. Only one of us spoke Spanish, so Laurel Marshall, our interpreter from CRISPAZ (Christians for Peace in El Salvador), the NGO that coordinated our visit, taught us to greet our hosts,“Mucho gusto, Mi nombre es…”

Each family emptied a room for its guests. For two nights, we Americans lay awake in their hand-hewn wooden beds, rooster calls reverberating in the hills. Parents and children rocked in crocheted hammocks that hung from common-room ceilings. After a fiesta lunch with village members—20 people to a side on benches, dining on chicken chow mein, tortillas, avocado and papaya—our group returned to the cool, dark adobe church. As Laurel interpreted, whited-haired women unravelled the story of mortars and troops that dropped from helicopters in the early 1980s, forcing them to abandon the village and follow the guerrillas into the hillsides. Families took food and gear to camp in the caves high above. But in the guinde (an untranslatable word that means something like big-flight), pummeled by constant bombing, they were left with nothing. They ate roots. Survivors fled to Honduras. Jesus Rojas, the name of their community, was the guerrilla name taken by the Nicaraguan priest who led the villagers out of a Honduran refugee camp in 1986, while civil war continued. When they returned, the Salvadoran military confined the campesinos in the ruins of their former church. The priest defended the villagers and lost his life.

Today, Jesus Rojas thrives as a village through intense practices of social solidarity. In the 1990s, women began working in a collective embroidery hut that still bustles. Crispaz sells their embroidery and jewelry. Women pool a portion of their earnings for visits to doctors and dentists. Villagers farm corn cooperatively. Parents save money for college expenses in a joint account which students replenish when they graduate. I made the mistake of giving my host family a jar of Nutella. “This kind of stuff makes our kidneys sick,” my host Esperanza Ortega responded. “We have no health insurance, so we don’t eat it.” When we asked to taste the local favorite, papusas—beans and cheese sandwiched inside tortilla batter, then grilled—five households cooked in a single outdoor kitchen. In this golden moment, the kingdom of God seemed alive on earth.

Just before the war, and shortly before his death, Romero made a final visit to Arcatao that Rosa Rivera vividly recalled to us. “When Monsenor Romero visited us in this church, the military forced him out of his car. We the women went to him. They kicked him as they let him come to us. When he celebrated mass here, there were three military guys at three doors. Romero said that day, ‘If we all work together, we can survive.’ Romero helped found the Office for Human Rights in the archdiocese. We sent him little notes about what was happening, and he denounced them on the radio.”

When Jon Sobrino reflects on the world’s hundreds of millions of poor and oppressed people, he calls them “the primary saints of the kingdom,” because he finds “primordial holiness” in their resilience to survive through repression, war, and refugee exile. This holiness arises from their ability to convene communities into existence to receive from one another mutual support: “Giving to one another and receiving one another with the best that one has.” Sobrino extends this sense of community further when he says, “Those who come from the world of plenty to help the poor repeatedly say, with thanks, that they have received more than they have given.”

On the walls of Arcatao’s church, the final Station of the Cross depicts resurrection. Rosa Rivera explained how international groups funded her community’s rebirth. NGOs affiliated with the U.N. accompanied villagers as repatriates from Honduran refugee camps and then supplied materials to rebuild. Churches, high schools and even whole towns around the U.S. and Canada continue to send money. “We relate international solidarity to the face of Jesus,” Rosa said. “Solidarity accompanied these people. For us, it was rest to have international solidarity. For those who love life, there are no borders.” Death, however, also came from outside the country’s borders. Salvadorans everywhere reminded us that in the 1980s, the U.S. financed El Salvador’s military operations against its own citizens, at a rate of $1 million a day. All munitions and helicopters were made in the U.S.A. Elite leaders who conducted the most savage massacres—like the 600 killed in the Rio Sumpul near Arcatao—were trained in Fort Benning, Georgia.

Martyrs accuse, offend and indict us. When Oscar Romero was most terrified, as he told his friend Maria Lopez Vigil, he made a desperate attempt to meet with Pope John Paul II. He showed the pope a photo of tank tracks crossing the head of a dead priest, young and newly ordained, but the pope only saw a communist guerrilla and looked away. U.S. President Jimmy Carter failed to respond to Romero’s urgent letter. Romero was only beatified in 2015, with the arrival of Jesuit Pope Francis. As El Salvador rebuilds, its divided country and church have taken decades to accept the central role of their martyrs. We were reminded of this each time we passed San Salvador’s Metropolitan Cathedral in the city’s central plaza.

In 2012, during his first week on the job, the current archbishop destroyed a campesino-inspired, tile mural that the country’s famed folk artist Fernando Llort installed on the cathedral facade to mark the fifth anniversary of the peace accords. On our last day, we sipped coffee in the cathedral’s inner courtyard with San Salvador’s auxiliary bishop. As we left, I mentioned that it pained me to see old photos of the beautiful tile masterpiece that the current archbishop had scraped from the facade. “It pains me every day,” the auxiliary bishop admitted. “But I do not think it would have happened today. The Church is learning.”

The greatest lesson I learned from Salvadorans was their fierce ability to look disaster in the face and name perpetrators and victims. One priest-turned-guerrilla, now married and serving a Morazán community filled with children and young people, told us, “The great matanza, slaughter, of the poor by the poor enables the Satanic capitalist system to eliminate those of us whom it deems unnecessary.”

“This mural is a story but also an analysis,” Rosa Rivera declared, standing before a larger-than-life painting of the 1980 Rio Sumpul massacre of 600 civilians—black bodies, caught between Salvadoran and Honduran armies, hold babies above the bloody river waters. Later, we walked to Arcatao’s white-washed sanctuario, built by a team of Dutch academics, where Rosa’s martyred parents are entombed. On the way, Rosa pointed to the house where soldiers had tortured her. Rosa does not believe in suffering for its own sake, but like Oscar Romero, she is determined that from suffering new life will arise. Asked which part of the mural was most significant for her, Rosa pointed to its single poinsettia: “For me, it is the flower, because we need to have hope for a better future. We have to live with pain, but not only with pain. If we consider ourselves always to be victims, we never become anything new.” Oscar Romero did not put his life on the line so Rosa Rivera might live eternal life after death, but to point to the way we all must live to ensure that Rosa and her people might thrive on their Arcatao hillside.

——

This article comes from material in my thesis, “Silencing the Martyr in Second Isaiah’s Suffering Servant,” where full citations can be found online at https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac:rn8pk0p2qg

In honor of Oscar Romero, seminarians from Union—Katie Reimer, Shep Glennon, Heidi Thorsen Oxford, Timothy Wotring, Rachael Hayes, and Liz Estes—are fundraising for a downpayment for a beautiful green hillside house to keep LaCasa Verde, an environmental art center, in Santo Tomas, a poor suburb outside San Salvador, so children do not need to stay locked up inside while their parents work, for fear of gang violence. Kids create, play, garden, snack, learn and have lots of fun with Norma Vaquero, the executive director, and young adult mentors who are artists and educators. Please help us! Donate here: https://www.generosity.com/education-fundraising/la-casa-verde-the-green-house

CRISPAZ (Christians for Peace in El Salvador) has partnered with Union for many years, hosting amazing journeys for January-term classes. They generously offered to act as fiscal sponsor to provide donors to LaCasa Verde with a tax exemption. Learn more about their good work at www.crispaz.org/