Bobbie Hart has lived in or near LaGrange, Ga., for her entire life; before 2015, she had never heard about Austin Callaway’s lynching. Like so many other acts of terror, Callaway’s abduction and murder in 1940 had been shrouded in suffocating silence, erased by the fear such despicable acts were designed to engender in LaGrange’s black community. That all changed when—while studying Union Professor Emeritus the Rev. Dr. James H. Cone’s masterpiece The Cross and the Lynching Tree—her friend Wes Edwards uncovered this devastating chapter in their town’s history, and together they initiated a years-long endeavor to confront the truth about their past.

Even “the Callaway family had very little information,” she told me. “It had been passed down on Miss Callaway’s side of the family that someone in the family was lynched, and it would come up at a family reunion, but they didn’t know much about it. They were just piecing things together too.” Indeed, Edwards notes how “that’s part of the way that [lynchings] were intended to work, to stoke fear.” As painful as it is to confront the depravity of a single lynching, it’s even harder to “realize that there’s so much more that we don’t know about.” This discovery, however, began a process of public dialogue and atonement that brought the town together to name this evil—and resulted in what is believed to be the first public apology from a police chief in the South forfailure to protect lynching victims.

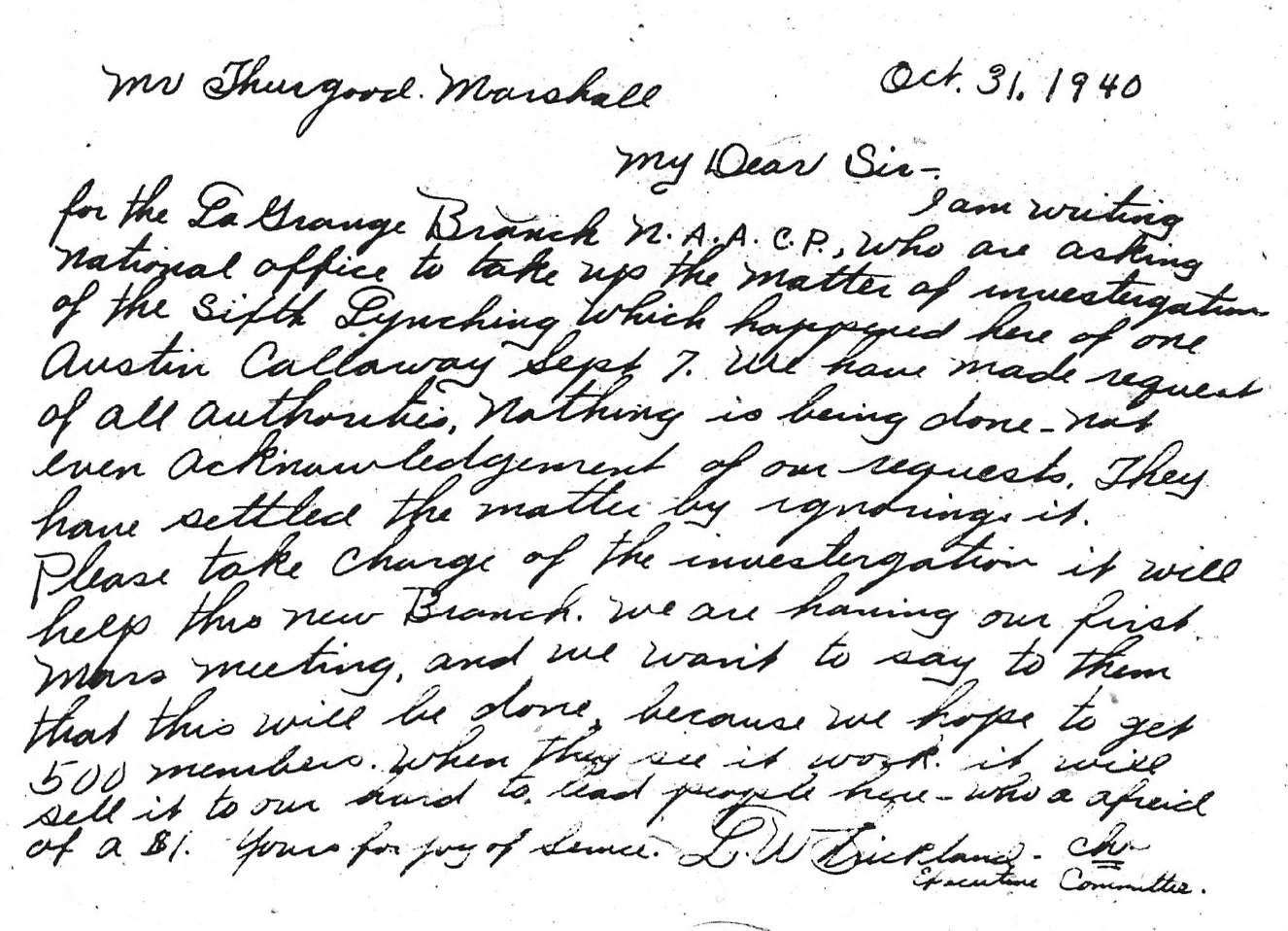

On October 31, 1940, the Rev. L.W. Strickland, then pastor of Warren Temple United Methodist Church in LaGrange, wrote to Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall about Callaway’s lynching: “We have made requests of all the authorities. Nothing is being done—not even an acknowledgement of our requests. They have settled the matter by ignoring it.”

Unfortunately, this disregard from civil authorities was all too typical. In TheCross and the Lynching Tree, Cone writes that between 1880 and 1940, “white Christians lynched nearly five thousand black men and women in a manner with obvious echoes of the Roman crucifixion of Jesus. Yet those ‘Christians’ did not see the irony or contradiction in their actions.” Far from recognizing the obvious scandal of the cross in their midst, many white Christians reveled in communal crucifixion, then banished its shameful legacy to obscurity.This blatant disregard for black lives compounded the tragedy of lynching and left festering wounds in towns across America. “You still see the effects of that system [of lynching] in La Grange,” Hart says. “You still feel the division.”

While obviously unable to rectify the profound evil of Callaway’s lynching, Hart and Edwards helped lead a group of LaGrange community members to expose and confront this neglected trauma. They founded Troup Together, an organization committed to investigating Troup County’s racial history and making the difficult journey toward reconciliation. Working with the current leaders of Warren Temple United Methodist Church, they organized a pilgrimage to Liberty Hill, where Callaway was lynched, and gave the man the funeral service he never received in 1940.

“When we arrived at Liberty Hill, I was amazed at all the people who had gathered in his memory. It touched me,” Hart remembers. “I was sad all of a sudden—it just came over me, this overwhelming emotion. I do remember saying, ‘I ask you, Father, to forgive the men who did this. Forgive the families, the ones who knew about it and did nothing. Just forgive the system that did this to Austin Callaway.”

After the service, Troup Together worked to ensure that the lynching of Austin Callaway would never again fade from public memory. They wrote to Police Chief Lou Dekmar, describing LaGrange public officials’ complicity in Callaway’s murder, and Dekmar responded by issuing a full-throated public apology. “This was brutal,” Dekmar said. “It represented injustice, specifically to an individual, and impacted a community generally because of the apprehension it created to deal with authorities. … I think an acknowledgement and apology is needed to help us understand how the past forms and impacts the present.”

Troup Together also worked with the Equal Justice Initiative to erect a marker at the Methodist church memorializing Callaway and three other men who were killed in the area: Willis Hodnett, Samuel Owensby, and Henry Gilbert.

“It was a real positive forthe community to have the public apology, to have the [memorial] marker, to have the leadership of the police department and the city and our religious leaders all acknowledge, apologize, and confess that this occurred and place the marker at Warren Temple,” Edwards says. “It’s now harder to silence that part of our history.” Hart, too, says the process not only helped plant seeds of healing in the community but deeply affected her personally. “It has made my faith stronger,” she says. “Dr. Cone, and this book, are bringing us back to Jesus, bringing us back to the cross. Today, that’s where I think we need to be. We need to stay right here.”

In June 2017, Professor Cone responded to a letter Hart and Edwards sent about their work in LaGrange, writing:

“I am very pleased to know about the influence of my book in the very important work that you are doing. I had heard about your work in the media, but it is quite another matter for you to write to me directly to say that my book played an important role as a discussion piece in acknowledging the lynching of Austin Callaway and more than 600 people in Georgia. I don’t usually respond to people who write to me about my book, but to know about your work helps me to know that the 10 years I spent writing it is indeed worthwhile.”

The work of organizers like Hart and Edwards testifies to the enduring power of Dr. Cone’s theology. His book’s true impact is not measured in sales, but in the prophetic justice movements it helped birth.

By Benjamin Perry