10 min read

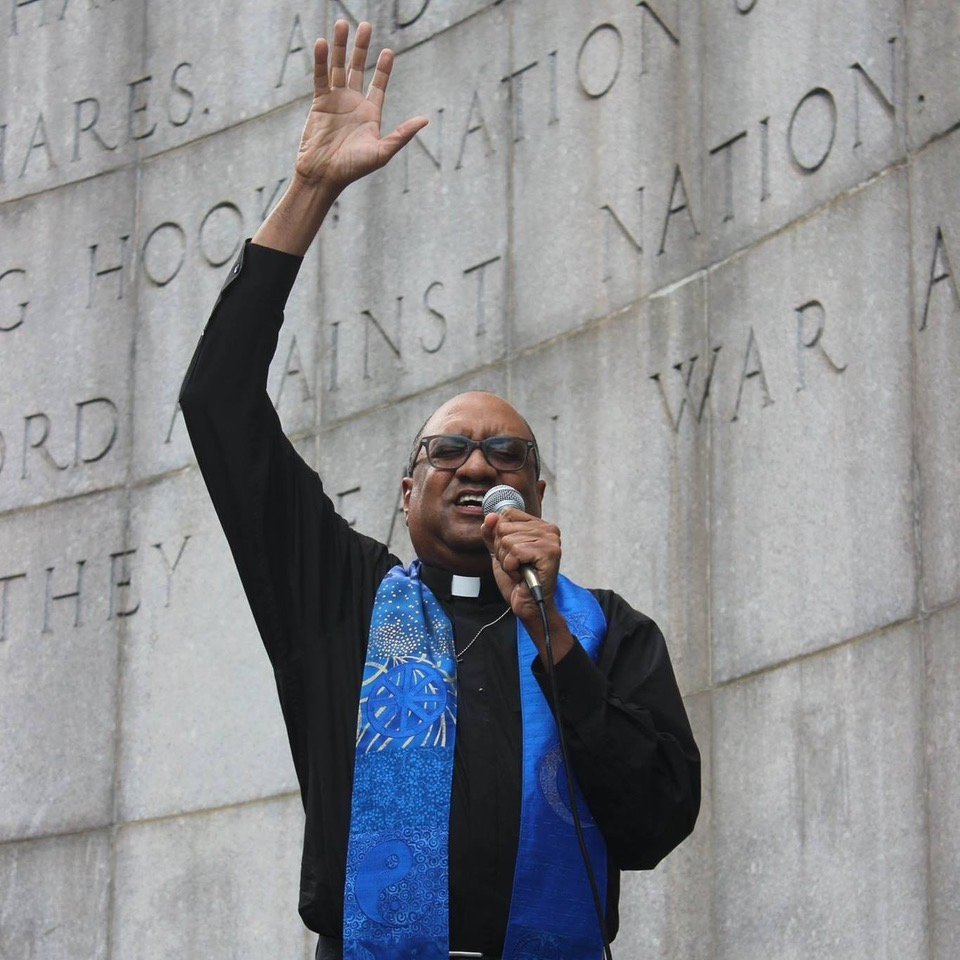

Union Alum the Rev. Dr. Derrick McQueen ’09, ’15, is the pastor of St. James Presbyterian Church, Board Chair of the Auburn Theological Seminary, and the Associate Director for the Center on African-American Religion, Sexual Politics, and Social Justice at Columbia University. In this interview, the Union and Auburn teams joined together to speak with the Rev. Dr. McQueen about his time at Union, his Presbyterian foundations, and his advice for future faith and social justice leaders.

Rev. Dr. McQueen, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us today. To start, can you tell us a bit about who you are and the work that you are engaged in?

I am the Reverend Dr. Derrick McQueen, and I am currently sitting as pastor of St. James Presbyterian Church in Harlem, New York City. It is the oldest African-American church in New York City and stems from the mother church, Shiloh, which was founded 200 years ago in 1822 and brought African-American Presbyterianism to New York City.

I am the first out and open, same-gender-loving pastor of an African American church in the Presbyterian Church here in New York City and [first] Senior Pastor in the country. I am also the Vice Chair of the board of Auburn Seminary, where I’ve been working with them in opening up programs for leadership for LGBTQ millennial and BIPOC persons to go into ordained ministry. I’m also the Associate Director for the Center on African-American Religion, Sexual Politics, and Social Justice at Columbia University.

That is amazing, several hats all at once! You’ve spoken before about the relationship between faith and social justice. Can you share why that’s important to you, and how faith informs social justice, or social justice informs faith for you?

It’s always been a tenet of my life—that faith and social justice are intertwined. I grew up in a Black community in Morristown, New Jersey,as a Baptist in a time period where the ministers were all abuzz about this new book called Black Theology [Black Theology & Black Power by James. H. Cone]. So I was six, seven, eight years old while all of these ministers in my hometown were figuring out how to have a voice as African-Americans and what that meant for social justice in our communities.

Growing up I would always speak to my mom about how she made it through being the first African-American bused to a school in North Jersey. She was bused to a high school away from her friends, away from her family, to integrate into a mostly white school. And that plays into these questions: even when there are places that people don’t want you in, how do you stand up and be there anyway?

I have always been very real about holding onto the ideals of the humanity and dignity that we all deserve. That’s always been my dream—for everyone to respect the dignity of everyone else, because dignity is at the base of justice. And in many of the things I do, I focus on dignity at the base of that justice. For example, I’m now working with a group in Schenectady as a consultant helping them with their feeding program, and helping them understand that the people that are coming for the food and the people giving the food are all equal partners in the food desert and the barrenness of food. It’s not “you’re giving from me and I’m taking from you.” We are all working together fighting against the injustice of food barrenness and food poverty.

This year I’ve been doing a lot of biblical work with my congregation and in the community about how the basis of righteousness is acting in the ways that God acts towards us. When we are called to act righteous and to be righteous, we are called to emulate the ways of God. I speak about this same energy with my friends who are Muslim, Buddhist, and Sikh. Our multi-faith conversations are anchored in that justice conversation so that we can all be in solidarity.

You are a Union alum. How did you decide to attend?

An alum of Union convinced me to go to Union! I was in Cape May, New Jersey, and I had just become Presbyterian and was working in a church. At one point the pastor got sick and I was asked to preach the next Sunday, and afterwards the Rev. Jo Tolley looked at me and she said, “You have to go to seminary, you have to go to Union, and I’m writing you a letter of recommendation to my preaching professor Jim Forbes.”

All my life I’ve had this dream where I’m going into this stone building and there is singing and I’m trying to figure out what it is. When I got accepted to Union I received a DVD where they gave a tour of Union, and as the tour was happening the music from my dream was playing. I got chills.

And then they walked up into the chapel, my chills got even bigger. In my dream, I would always wake up before the chapel opened, but in the video they opened the doors to James chapel and it was the completion of my dream. It was the same stone building, the same song, that I had seen in my dreams since I was sixteen years old.

That is amazing—from the person who said ‘this place is for you, I’m going to put you in touch with the community,’ to answering this subconscious pull from your childhood. You said that you were a new Presbyterian just before all of this happened. How did you get into that tradition?

It was the polity. I am a firm believer in the aspiration of democracy. We may not get it right, but we can aspire. If we can get it right, it will be so beautiful. Polity is the opportunity to sit down and be in discernment rather than quick decision making. Polity also gives a place for the minority voice to be heard. The minority voice is very often the working of Spirit to help shift things and create change.

[I also came into Presbyterianism] when I was at a church in Cape May. There was a certain apex in my ministry where I lived the experience of polity and theology all working together. Beautiful things happened with the Spirit. If I can work towards that happening again in my lifetime, or work towards making that happen for anyone else, then I’m willing to spend the rest of my life doing it.

What is your relationship with Auburn, and how do you find being at a multi-faith seminary that has Presbyterian roots helps you as a Presbyterian minister practicing in a multi-faith society?

One of the major persons on our board and in the Presbyterian church, Janet Edwards, is very articulate about the ideals of Presbyterianism that are in our Book of Order, and says that they demand for us to be multi-faith and open to communities. I went to Cuba twice, and when I asked the minister of the first Presbyterian church of Havana why Presbyterianism took off in Cuba, he said, “Other denominations came and said ‘We won’t feed you unless you believe like us. We won’t give you medical care unless you believe like us.’ Meanwhile, the Presbyterians opened schools and said, ‘All are welcome.’” You find the common language to address the ills of the world.

That catapulted me into multi-faith work in a big way. And I see Auburn as the living embodiment of that in the community and in the world.

What it was like for you to attend an affirming seminary, and the importance of Union being an affirming seminary?

To be honest, Union being an affirming seminary did not factor into my applying. I was on a spiritual journey to answer a call and was led to Union. The fact that it is an affirming seminary was a powerfully moving confirmation of the Spirit that I had discerned and listened to my call. The fact that Auburn was also a stalwart ally for justice and affirmation for LGBTQ+ persons in the PC(USA) denomination, which had not yet voted to affirm, was yet another gift. And as an African American, that Union had an existing organization for LGBTQ+ persons of color was a deep theological representation of trinitarian relevance at work in my life.

In 2006, I felt that to be a queer-identified minister would sound something like “I am queer but I am a minister.” You know, the apologetics would have to go hand in hand. But Union and Auburn allowed me to articulate clearly, “I am queer and I am a minister.” I can bring my full self to ministry.

You’ve mentioned a really beautiful breakthrough moment you had in Christopher Morse’s class. Can you tell us more about your time at Union?

I started at Union in 2006 and graduated with my Ph.D. in 2015—so I have so much to say! I joined the worship community, sang, fell in love with ritual and liturgy, and was a Student Life Assistant (SLA). As an SLA Michael Orzechowski and I worked a lot with helping to shape the parameters of the community. There were very deep times in doing that work, and finding ways to address challenges as a whole community was really powerful for me.

And I worked with Barbara Lundblad and Hal Taussig for my Ph.D.—I mean, come on! Here I am thinking I’m doing a Ph.D. in homiletics, and then all of a sudden I’m doing it just as equally in New Testament. To be able to have a space to break ground like that at Union Theological Seminary was really powerful—to graduate being a one-man preaching and worship department.

The theological and the personal all came together for me in Christopher Morse’s class at Union, in Room 207, when he said, “Sin is nothing more than a separation from God. So break whatever is keeping you separated.” It freed me.

Many of the professors I encountered at Union are fully cognizant of the fact that while you are a student you are going through a shift of spirit, mind, personality, and of who you are. Union professors give birth for that to grow, and then Auburn really fans the flame and says “go!” They work in tandem with one another. I also have to give the plug once again to the polity course chorus at Union that is done by Auburn staff person and Union Alum Greg Horn ’91 (Union ‘91). The way that Union allows you to find what your voice is helps you define your voice within the Presbyterian denomination. It’s about expanding liturgy so that we can speak to justice and righteousness—whether it’s Presbyterian, Jewish, Muslim—it’s about fine-tuning that and being able to have what James Cone says is “finding your voice,” and then being able to use your voice within the structure of your denomination.

You’ve told a lot of stories about professors or mentors who have held your story or helped you navigate a shift. Can you share a bit about what you hope for the future of pastoring?

I’m really excited about the future of pastoring as we move through this next shift of heart and language reformation in mainline churches. The saying is that mainline churches are dying. I don’t think they’re dying. I think they’re reshaping themselves.

I studied a lot with the Book of Revelations, and it doesn’t say that a new heaven and new earth has to wipe away everything else. It says that God cuts away one third of everything that needs to go, in order for there to be this river and this city and these trees that can feed everyone. You have to cut away that which is no longer useful.

I think the future of pastoring is in identifying the fact that every person has a ministry, and that the pastor is the shepherd. Being in relationship with people expressing what their relationship to the divine is—how is that calling them, and how can I help you? And it branches out into the community. Many of us on the ground don’t have money to do all of this outreach, but we do have the ability to make connections in the community and assess what the needs are and offer spiritual support. The future of pastoring is sharing how pastoring is answering the particular needs of the community.

What advice would you give to young people who are curious about what you do and want to follow you in working at the intersections of faith and social justice?

There is one piece of advice I would give to everyone because I think it’s just one of the most important things I’ve ever learned. In Obery Hendricks’ book, The Politics of Jesus, he talks about the seven strategies of Jesus’s ministry. And the first strategy that I think is most important for people who are working in faith and social justice is that Jesus saw and recognized and claimed people’s needs as holy and sacred. People’s needs are sacred.

When you hold onto that, everything you do in your faith journey and everything that you do with social justice comes from that. It’s holy for people to be full with food and have their needs supplied, to have homes, to have houses, it’s a holy thing. You can revert all the way back to creation: that’s why God created so that everything would be there for these creatures that God loved. And that is a holy thing that we’re trying to get back to.

So I would tell everyone to take that idea and go into meditation and discern what it means to really understand deep down—to see people’s needs as holy, whether you agree with them or not, but to know that those needs are holy nonetheless and to grow into that.

Thank you, Derrick. Is there anything else that you want to share?

I would share that in building your portfolio of faith and how that intersects with social justice, to always do two things. Let yourself be in discernment about the transition you find yourself entering. Transitions are not something that happen overnight. There’s a trajectory of transitions and we’re always in transition one way or another.

When I first found out that I got into Union’s Ph.D. program, I was in the stairwell by the library with Serene Jones, and she said, “So how does it feel to be a Ph.D. student?” And I said, “Quite honestly, I’m not going to claim that until I finish with my Masters.” I wanted to complete that before I conflated the two identities I needed to transition from one to the next. Taking that time is really beautiful.

The second thing that is of utmost importance is self care. Not just going on vacation, not just “Netflix and chill,” but self care for your spirit. To know that this work is hard and traumatic, and that the trauma will revisit you when you least expect it. But to take care of yourself and be a model for how we take care of ourselves when the opportunity comes, when we start to feel something is off, and say, “I need to step back for a moment. I need to take a walk. I need to go to another church. I need to talk to a therapist.”

Take care of yourself. Because when you are working in social justice, you are working with people who this matters for. And it’s a matter of life and death. Being on the precipice of life and death is traumatic and pulling people back from that precipice—you can’t drag them. You can only do it by saying, “I do the same thing. Let’s do this together.” So self care, full self care, is key.

One of my biggest forms of self care is cooking. I cook things that take a long time to make so that if people say “Can you get on this Zoom?” I say “I can’t, I’ve got this sauce on the stove!” I do things that are going to take an inordinate amount of time. If I’m in a rush to take an Uber, I’m going to take a bus, I’m going to walk through the park. It’s mostly taking the time that you think you don’t have.

Thank you for being open to giving in this way. These are stories that people need to hear.

Thank you. And confirmation does come, you just have to be open to it. When the Rev. Dr. Calvin Butts showed up at my installation, he came out of the blue, and he said, “I just want to say something.” And he told the community that was at my installation, “We have been watching this young man since he first came to our pulpit in 2006 when he entered seminary. We are in full support of him.” It weakened me. It was a public affirmation, not just of my ministry, but in a community where he was saying this about someone who he knew was openly gay. And that’s big. Full circle.